Joining the ranks within the profession of law enforcement, whether on the local, state, or federal level is honorable and courageous. Men and women across the nation are taking their oath of office, swearing “to protect and to serve,” proudly pinning on their new badges, strapping on their gunbelts, and stepping out into a different world. There’s a certain excitement that goes with that very first day when you walk out the door of your station house, and become a part of the war on crime. Beware the dangers: Just about a step and a half on the other side of the sanity you hold dear, is a dark side. Like a steel-jawed trap, it lies in wait for the unsuspecting—the unprepared, and if you aren’t careful, it can rip the life out of you. The dark side can change your life in the blink of an eye, or over time, depending on the strength of its grip, and your vulnerability to it. You can change to the point where friends don’t know you any more, and to your own family you become a stranger.

A husband or wife might wonder what happened to that person they married, while your children ask who you are. There are some that spiral down into the deepest recesses of the dark side, and when their entire world suddenly seems hopeless, they “eat their gun.” Now, those left dazed and alone, without a husband and father, or wife and mother, try to find the answers to “What went wrong?” or “Why?”

Maybe there’s a genuine confusion that mixes reality with fantasy. Police shows have swept across the country for decades, and it seems that people can’t get enough of the shoot ’em up, chase ’em down spectacles that flash across the screen. From the very old days of Dragnet and Jack Webb’s, Sergeant Joe Friday, to last night’s CSI and William Petersen’s, Gil Grissom, we are fed almost daily doses of “Police life.” The problem is, far too many people can’t separate the fictional from the genuine world of those who risk their lives day after day, doing the job. And, some of those confusing the issues might very well be the same ones rushing to find a job enforcing the law. The real world was becoming lost, when the police shows of the early 70s, with their rock music introductions, and drum thumping car chases, infiltrated our living rooms. Steve Forrest, and his gang from S.W.A.T., roared around town in a big black van, shooting bad guys and saving the day, and never wrote a single police report.

Today, with CSI, everybody believes a DNA test is concluded in only five minutes or so. Well, in the real world of law enforcement, it can take months before the results of a DNA test come back. Other shows depict the suspects being beaten with fists, knees, and telephone books in the interview rooms to extract a confession. That might make for a good television, or movie theme, but if it happened in the actual police world, the officers or detectives responsible would be facing criminal, as well as internal charges. Howard County State’s Attorney Tim McCrone, is disturbed with the screen dramas that continually have police beating a confession out of a suspect. “This is far from the truth, but I’m afraid we have jurors who think this is the way officers obtain confessions,” he said. “Certainly any confession obtained by these methods would be inadmissible in court.” Yet, there are those who believe CSI, Law and Order SVU, Numbers, Criminal Minds, and the dozens of other shows are absolutely true. Indeed, some of these shows go above and beyond showing the plight of the many victims, but we still have to separate fact from fantasy.

The true-life world of policing has a certain air of ugliness attached to it. Always has, but not many people see it. Maybe this is why so many law enforcement officers are taking their own lives. A recent report on AOL News showed an alarming figure of 450 law enforcement suicides in each of the last three years. That’s a staggering number when you think that on the average for the same time period, 150 officers were killed in the line of duty. Think about it—more officers are taking their own lives than are being killed by suspects they encounter. Why? Someone pointed out that “police bear the

same stress from work, family, and illness that civilians do.” That statement is an absolute falsehood. The stress level in law enforcement far exceeds anything in the civilian world.

Police officers and federal agents, struggling in the war on crime, find themselves facing real guns with very real bullets. They walk around, and through the stench of death, and bloody mess it so often leaves behind. The smell of death saturates their uniforms and clothing, providing them with a reminder for hours on end of where they’ve just been. They spend hours with broken, mangled bodies, while loved ones or friends of the victim scream at them to do something to find the killer. They can kiss their wife goodbye, and an hour later they can be looking over the aftermath of a head-on collision, trying to figure out what body parts belong to which passenger.

They can kiss their children goodnight, and minutes later find themselves staring at the corpse of a child who was just molested and murdered. Crimes involving children have always hit law enforcement officers hardest, and some are effected so deeply they end up taking their own lives over the horror they saw. Some officers work full time with cases involving children. I strongly doubt that I could’ve worked cases with child victims. I don’t think that I would have gone a week without killing a suspect. When police officers leave the blood, gore and mayhem, they can sit down at a desk for countless hours, and write the required reports.

That way they can relive all of those details they’d just as soon forget. When they go home and fall asleep, they’ll probably get to recall it all again in one of the endless nightmares that are sure to come. Nightmares go hand in hand with a career in law enforcement, and every street cop will have more than his or her share of them. It’s almost as though the nightmares were a part of your standard issue, and you signed for them the same as you did your badge and gun. Those hideous dreams won’t go away when you leave the job either. In time, however, they just won’t show up as frequently. But, don’t let that lull you into a false sense of security. When you least expect it, one will knock at your dream door, and dump all of that blood and horror you thought you’d finally left behind, right there on the pillow beside you.

Law enforcement officers don’t walk around in suits that cost thousands of dollars and rub elbows with the corporate elite. But, they will get to share lots of their time with pimps, hookers, drug dealers, and drug addicts. They won’t be invited to State Dinners, and banquets attended by movie stars, and sports heroes, where seven course meals are served. Instead, they’ll try and swallow a cold slice of pizza, or what was at one time a hot pastrami sandwich, while they sit in some godforsaken place, watching the back door of a construction company. People won’t rush over and beg for their autograph, but they’ll find some that are only too happy to spit in their face.

While corporate executives, the self-made millionaires, and others in the normal business world gather around with their family for Christmas dinner, the police officer might be responding to their very first call of his or her shift. When that same executive is reaching for another slice of pie, the police officer could be asking a drunken man why he stuck a butcher knife through his wife’s heart, and left her beside the Christmas tree. At the same time, other officers are trying to take three or four kicking and screaming children, who are covered in their mother’s blood, from the house. And somebody really thinks the stress levels for police officers and civilians are the same.

Still, we’ve only scratched the surface of the stress thousands of officers, and agents deal with every day of their lives. Some work two jobs to try and make ends meet, because their police salary is too meager. The pay scale has improved for some police agencies, but not all of them. Many will have to work swing shifts, and the constant rotation of schedule can take its toll physically, and emotionally. After working all night,

they could find themselves headed to court for traffic or criminal cases. A few hours in court, a couple hours of sleep, and they’re back at work. Oh, and what happened to their family life? Maybe they are becoming that stranger who stops by to say hello from time to time. How much time can a husband share with his wife and children? What about holidays—like Christmas, will he or she have to work all of them? How many officers can expect to have weekends off? And mother’s wearing the badge and gun, are they seeing their children as often as they want? How much quality time are they having for their children? Do they have enough time to tell them how much they love them? Are their children pleading with them to stay home, and spend more time with them? How many begin to feel guilty because of the time they’ve lost with loved ones? Do you think any of them might be trying to drown their guilt in alcohol? You don’t think they’d pop a pill to help them feel better, do you? Will they come home from work one day and have their spouse say, “We need to talk?” Then the bomb drops, “I can’t take this any more. I want a divorce.”

Then again they could just say, “Pack your bags, I want you out of here.” Or, maybe like some police officers, they come home and find their house is empty—everything in the house is gone, right down to the very last piece of furniture, rug, lamp, and even the dog. Believe it or not, some of them didn’t even see it coming. Standing alone in their empty house, they try to understand what’s just happened to them, and the life that seemed great only hours ago when they left for work. Where do they go from here? Who do they turn to for help? Will they hold it together, or fall apart? Will they take the final plunge, and eat their gun?

The internal workings of an agency can up the stress level as well. From small departments to large, there’s always somebody who is looking to rise to the top, and by whatever means necessary. They don’t care about the games they have to play, be it politics, keeping the rumor mill rolling, or the quick knife in the back of another officer, or agent they see as a threat to their success. Some act in liaison with others, and they form a clique, knowing they can ride certain coattails to the top of the ladder. Yet, when they reach the top, they can suddenly forget those who helped them reach their pinnacle of achievement. It’s amazing how fast they can slam that door behind them, and right in the faces of those they had promised to help. And don’t be surprised if you find there’s a double standard within the ranks. Rules that strictly apply to most of the rank and file are overlooked, or completely forgotten when it comes to applying those rules to “one of the good ole boys.” And it might shock you to find what some people can get away with. The internal operations of an agency can often times cause more stress on its officers than everyday duties. I’ve heard officers say, “I’d rather deal with a suspect than a lot of guys in the department. At least I know what to expect from a suspect.”

Promotional processes are not always fair, and when politics enters the game, even the most unqualified can be promoted. Internal and external pressures have caused test scores to be changed, so a favored son or daughter, who didn’t do well on the exam, can suddenly have a passing grade. New positions are often created for them, because they are too incompetent to function in a supervisory capacity on the front lines. And, some favoritism is so blatant, it screams to everyone eligible for promotion, that they don’t stand a chance for advancement. Case in point: A man is directed to put together the written examination for the rank of sergeant. He compiles the test questions and takes the test along with everyone else on the eligibility list. And wouldn’t you know it, he got a perfect score and was promoted. This is a typical example of how morale is destroyed within an agency, and implants a cynical attitude within the ranks. It adds up to just one more stress factor in the lives of the men and women who are trying to protect and serve.

There are Chiefs of Police who are making commendable efforts to correct the problems dumped in their laps by their predecessors. It won’t be easy to improve the internal image of a department that’s suffered from “good ole boy” syndrome or the

double standard game. But, those problems can be fixed, and a sense of fair play can go a long way toward improving morale, and reducing at least one stress element facing its officers.

When everything is considered—the horrors of the job itself, the pressure placed on the entire family to adjust to a law officer’s life, the working hours, the salary, and the internal tension faced by many—the stress faced by law enforcement officers, far exceeds that in the civilian world.

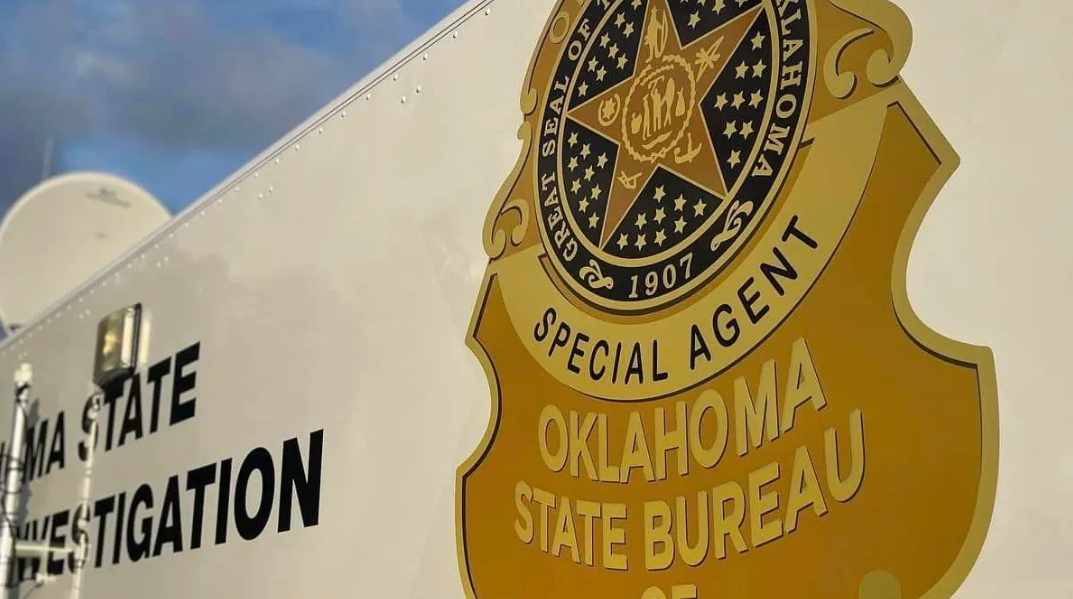

Police agencies across the country are becoming more aware of these issues, and working diligently to institute programs to assist their officers. Many agencies already have crisis intervention teams to assist officers, and their families through troubled times,

but there’s still a very long way to go. The California Highway Patrol, for example,

faced a major crisis when eight of its troopers took their lives in a period of eight months.

Of course, it isn’t always easy to get some officers to admit they have a problem, or are in need of help. Many who are asked if they are experiencing problems with drinking to marital issues, deny it. This stems in part, because of the image of the job, and its inference of strength and control. Then too, there was the long time theory that police officers weren’t supposed to show emotion, or let the job beat them down. In recent years that theory has been pushed aside. Still, many are afraid to ask for help, because they think it’s a sign of weakness.

Some friends have asked if any of the problems facing modern day police officers were created, at least in part, by the early police dramas. I can’t give a definitive answer to that question, but let’s face it; there was an over abundance of Macho cops running across the screen every week. It wasn’t until the early 80s, and the arrival of Hill Street Blues, that we started to see some actual vulnerability in our TV police officers. Now, we see them in counseling and working to fight their demons.

It’s not easy being on the front lines and dealing with these issues. Unfortunately, I knew a police officer who took his own life, and I knew him quite well. I met him when he was a cadet assigned to my squad in the radio room. He was a good kid, and I doubt that he’d ever been in trouble a day in his life. He’d often run with me after work while preparing to enter the police academy. He was on the fast track to do well after he graduated from the academy, and soon found himself in the Criminal Investigations Bureau. I didn’t know he was having problems, and I’m not sure if any of his coworkers were aware that he’d been drinking more, and involved in some domestic issues. On a Thursday afternoon he asked me if I had time to come down to the weight room and teach him a few new exercises to work his arm muscles. I spent about 15 minutes with him in the weight room and an hour or so later he stopped by and thanked me. Around 4:30 Sunday morning I received a call telling me that he’d killed himself. I was stunned, but I believe his death rocked the entire department from the top down. And his death wasn’t something everybody got over in a week or two.

Over the years, I’ve dealt with at least a half dozen officers who were on the brink, facing personal disaster. I admit to having more than a few sleepless nights wondering if I’d made the right decision, or gave the correct advice while talking with them. Although one kept me on the edge for weeks. I saw his problem from the very beginning, when he began hanging around with a newer cop who already had a bad attitude. It wasn’t long before the drinking took over, and soon his attitude went down the drain, along with his marriage. Everything he did and said told me he was suicidal, but what worried me even more was the growing feeling that if he snapped he wasn’t going out of this world alone. I was afraid he’d kill his wife and children before killing himself. There were a lot of very hard decisions I made over the course of two or three weeks, but I thank God they were the right ones. In the end he left the job, dove head first into the booze, his marriage finally fell apart for good, and he didn’t live to see his 50th birthday. As for everybody else, they turned out fine.

I sometimes joked that in police work you walked a fine line between sanity and madness. Yet, that statement might hold more truth than fiction. We have to deal with the good, the bad, the heartbreak, and death. Most police officers will see enough of that to last several life times. Still, when I hung up the badge and gun I said, “If I could turn back the hands of time and start all over tomorrow morning, I’d gladly do it all again, without question.”